One of my senior students once came up with what he called the “Bulls*** Theory.” His idea was simple: if you haven’t studied (and he rarely had), use the question as a springboard to craft the most elegant, formal, and fluent English you can muster, and fool your examiner into thinking you know what you’re talking about.

Now, I certainly don’t endorse this approach, but there’s something to be said for his reasoning. The person who sets your question isn’t out to get you—they want you to succeed. In fact, they often provide subtle hints and guidance to help you along the way. Let’s take a closer look at how these cues can make your academic writing process smoother and more successful.

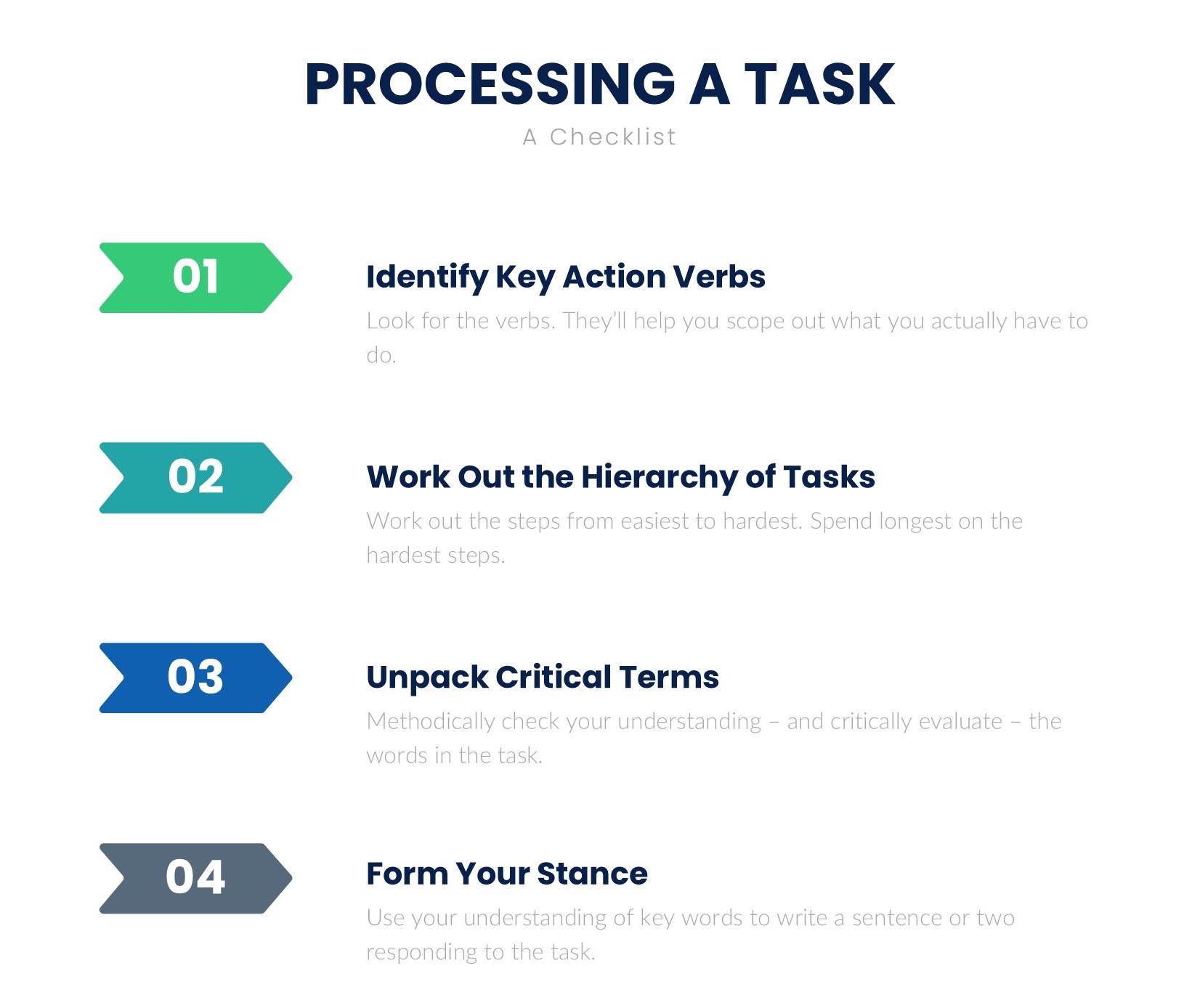

Follow the Clues in the Task

First and foremost, always pay attention to the instructional clues in your assignment. Often, these instructions offer a clear roadmap for how to structure and organise your response. For instance, consider the following task setup (I’ve deleted any indicators of subject or level):

Table 1

|

This structure is typical of well-designed tasks in subjects where content knowledge is key, and the writing itself is secondary. You’ll notice that the questions are arranged in ascending order of complexity – you start with a list and end with your own thinking. Ignore this clear structure at your peril!

Deciphering Complex Assignments

Other areas of study, like my own subject of English, often require students to independently form opinions and arguments with far less guidance. However, even in these cases, clues are embedded within the instructions if you know where to look.

It’s easy to overlook the instructional guidance because it’s often placed above the questions. But there’s gold in those words. Let’s explore an example:

Table 2

| EXPLORING ISSUES IN LITERATURE AND LANGUAGE |

| Write an essay in response to ONE of statements 10–16 below. Use the statement as the focus for an in-depth discussion of a range of texts. |

| Note: No content or quotations used in your answer to Section B should be repeated in this section. |

What we know:

- The essay must be in traditional essay form (no subheadings, with an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion).

- We need to identify an ‘issue’ to discuss, and we must consider multiple viewpoints (‘explore’).

- We must respond directly to one of the statements, essentially forming one half of a formal conversation. This provides a useful approach to the thinking—imagine someone’s arguing with you.

- We need to focus on the statement, privilege critical thought, and reference at least three (‘a range’) of texts.

We know all of this before even reading the specific statements. The assignment’s instructions not only guide the structure but also suggest the depth of thinking required.

The Thinking Behind the Task

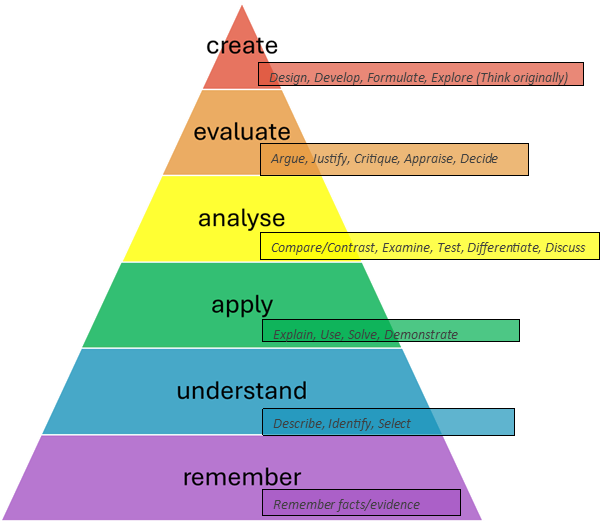

The second part of any assignment revolves around what you’re being asked to think about, and how. Referring back to Table 1, the initial thinking required is simple: merely ‘identify’—in other words, can you recognize something? As you move through the task, more complex thinking is demanded, such as evaluating choices or providing evidence-based explanations.

The final section – ‘What happens next and why?’ requires the most in-depth thinking – you’re asked to extrapolate from what you’ve already discussed to imagine its consequences. It’s asking you to synthesise what you know. However, again, you’re led up the ladder of expectation clearly, so as long as you’re aware of the signposts (the significance of those ‘thinking’ words), and you’ve done your research, you’ll be fine.

Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy

How Instructional Words fit in the Hierarchy of Thinking

Once again, while this structured approach is helpful, not all tasks are so clearly mapped out—especially in subjects like English. In these cases, the key to success is in slowing down and thinking deeply about the meaning of the words in the question.

Breaking Down the Question

Let’s take this question as an example.

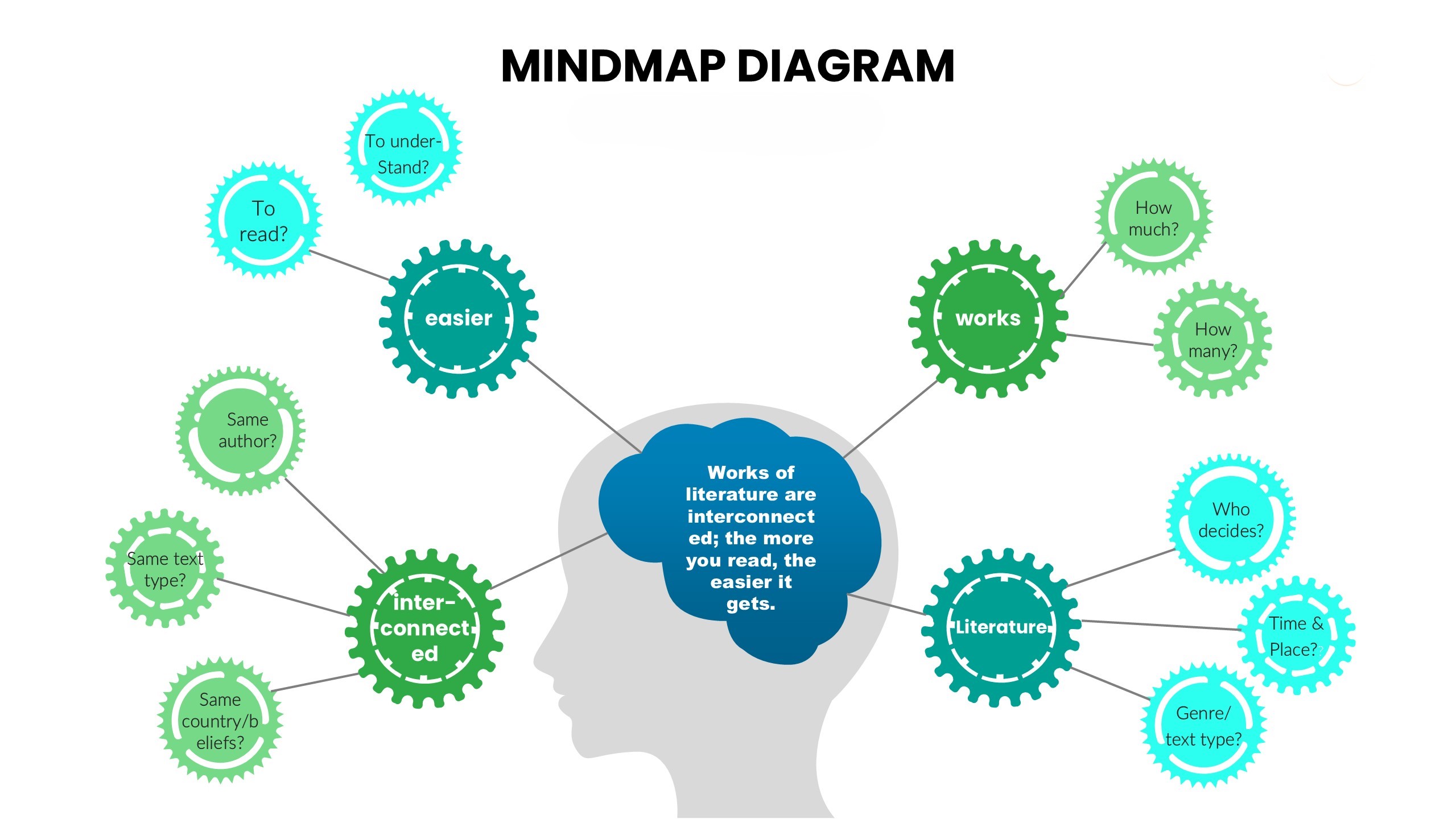

“Works of literature are interconnected; the more you read, the easier it gets.”

At first glance, the words seem straightforward, and it’s difficult to see how you might extract a thoughtful, in-depth essay. The place to start – and I can’t stress this enough! – is by thinking deeply about the meaning of the words in the question. Jut stop and consider – don’t assume you know the full meaning of a word and glide past it.

For example,

- What’s a ‘work’? We might all agree that a play by Shakespeare qualifies. But what about a modern poem? Is that enough to be a ‘work’? Or are we talking about a book of poems?

- What counts as literature? Shakespeare is a given—but could you make an argument for a lyricist? Bob Dylan won the Nobel Prize for literature, after all. So who or what makes that call?

- What does ‘interconnected’ mean? Does it refer to connections between works by the same author, or perhaps within a single book? Or is it broader than that – works produced in the same country, or by members of the same culture?

- What does ‘easier’ mean in this context? Does it mean easier to understand? Easier to complete? Easier to interpret?

Whether your starting point for this essay is “The more of a culture’s great works we have read, the more we understand that culture,” or “A poem cannot be fully appreciated in isolation: understanding becomes easier the more the reader experiences of the poet’s voice,” you can see how unpacking the question in this way leads to a well-grounded stance or opinion—one that is based on an in-depth understanding of the question.

Final Thoughts

You’ve likely heard, throughout your academic journey, about the importance of slowing down at the start of an assignment or exam. I hope this exploration has shown you why it’s so essential. By taking the time to carefully analyse the instructions and think critically about the words in the question, you can set yourself up for success, turning what might seem like a daunting task into an opportunity to showcase your understanding and insight.